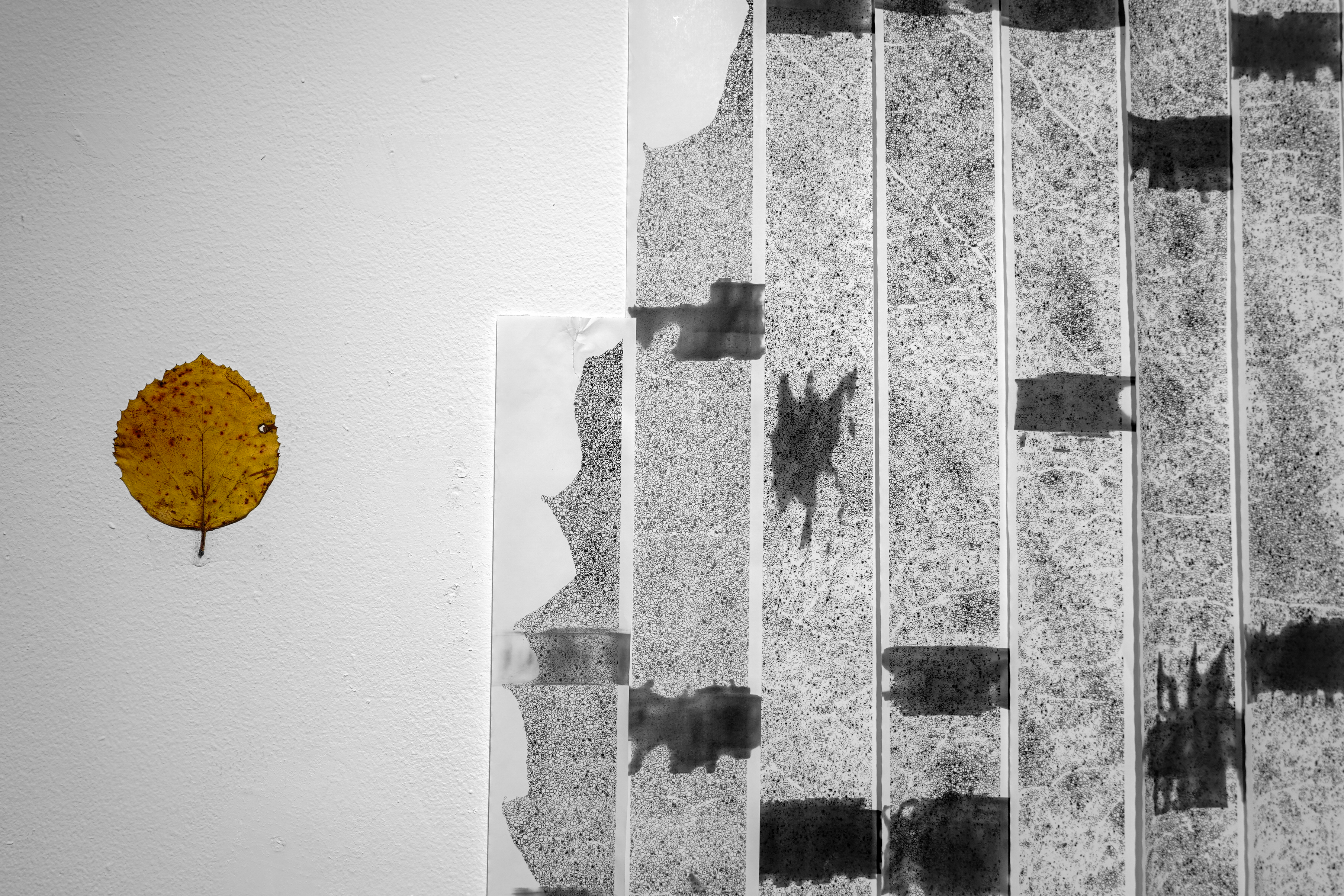

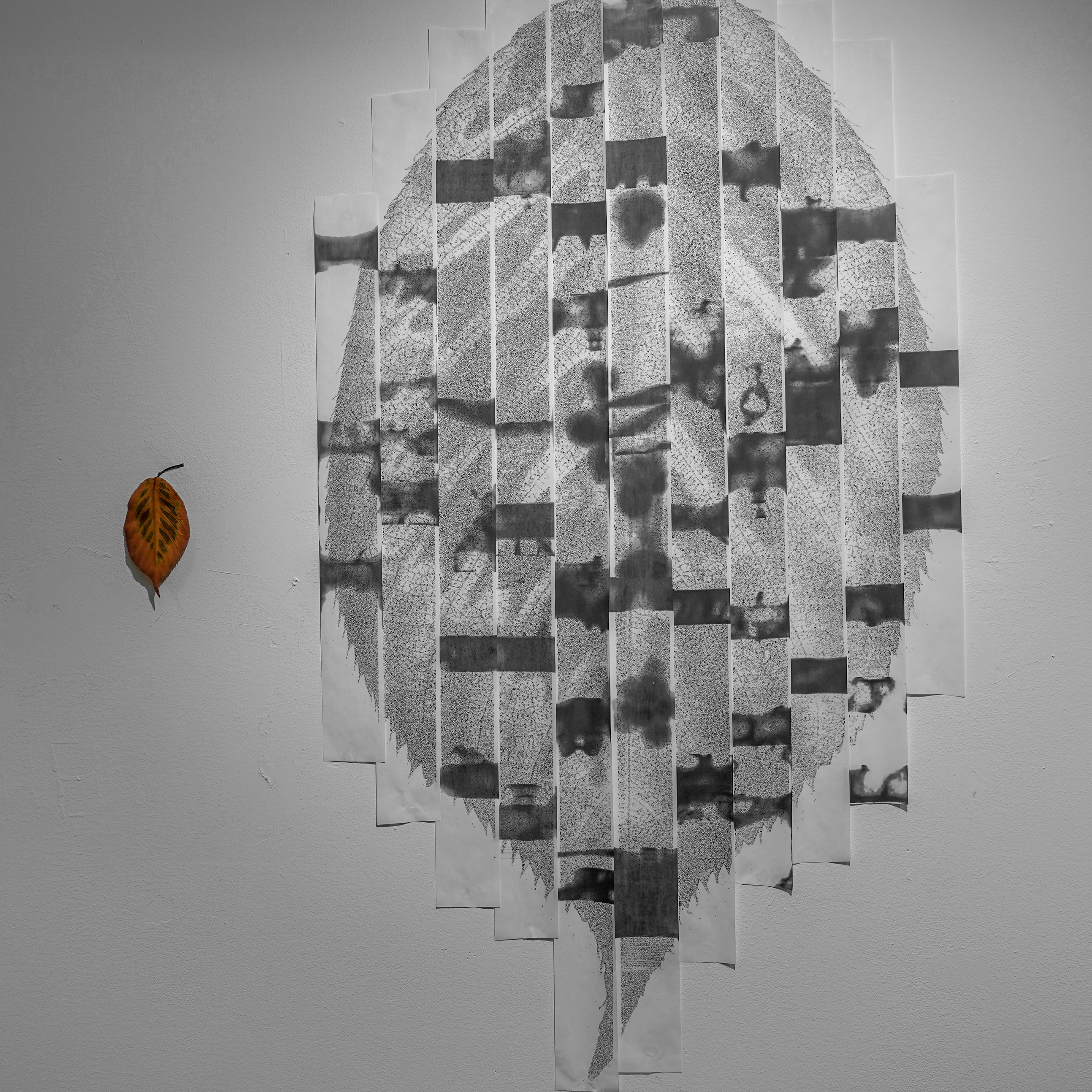

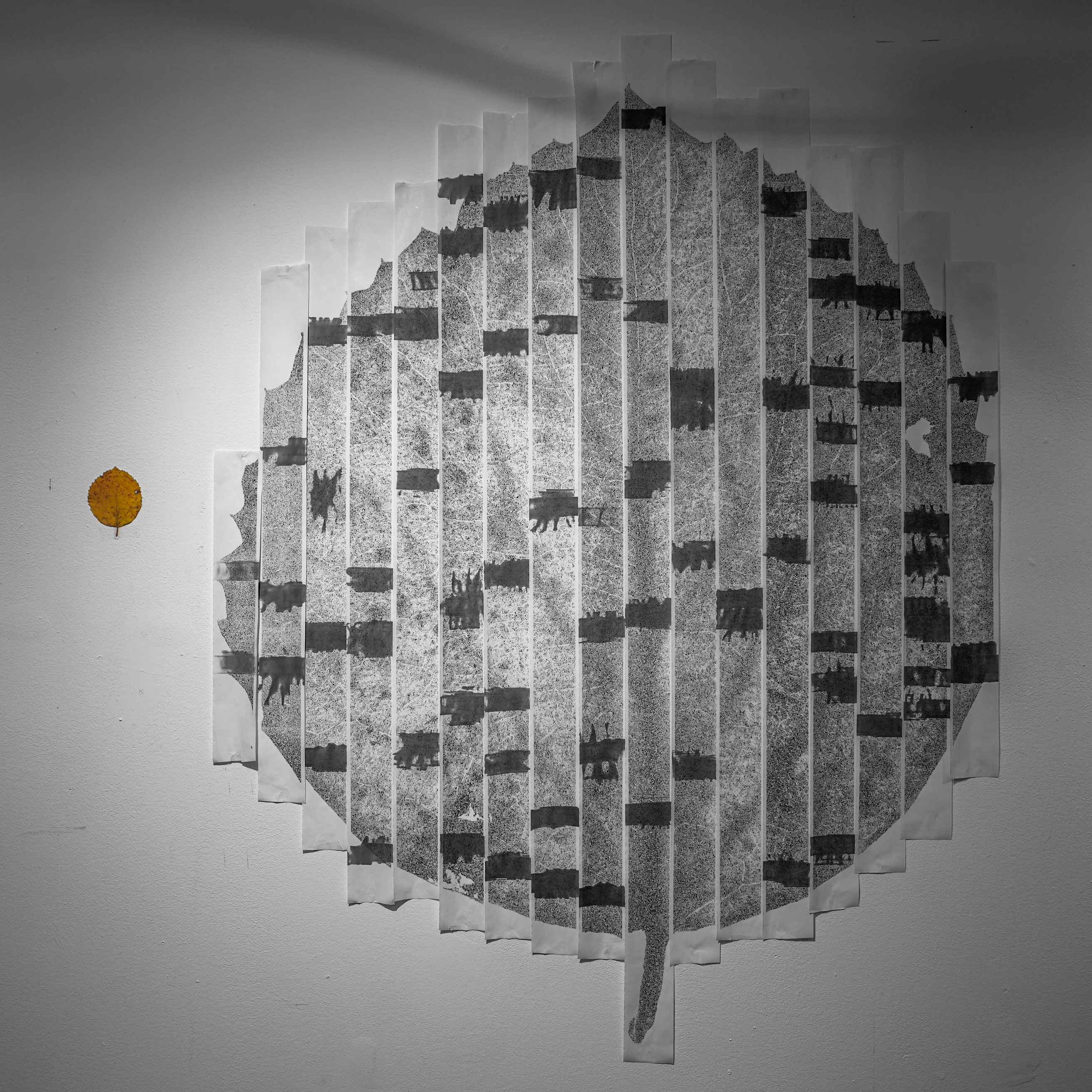

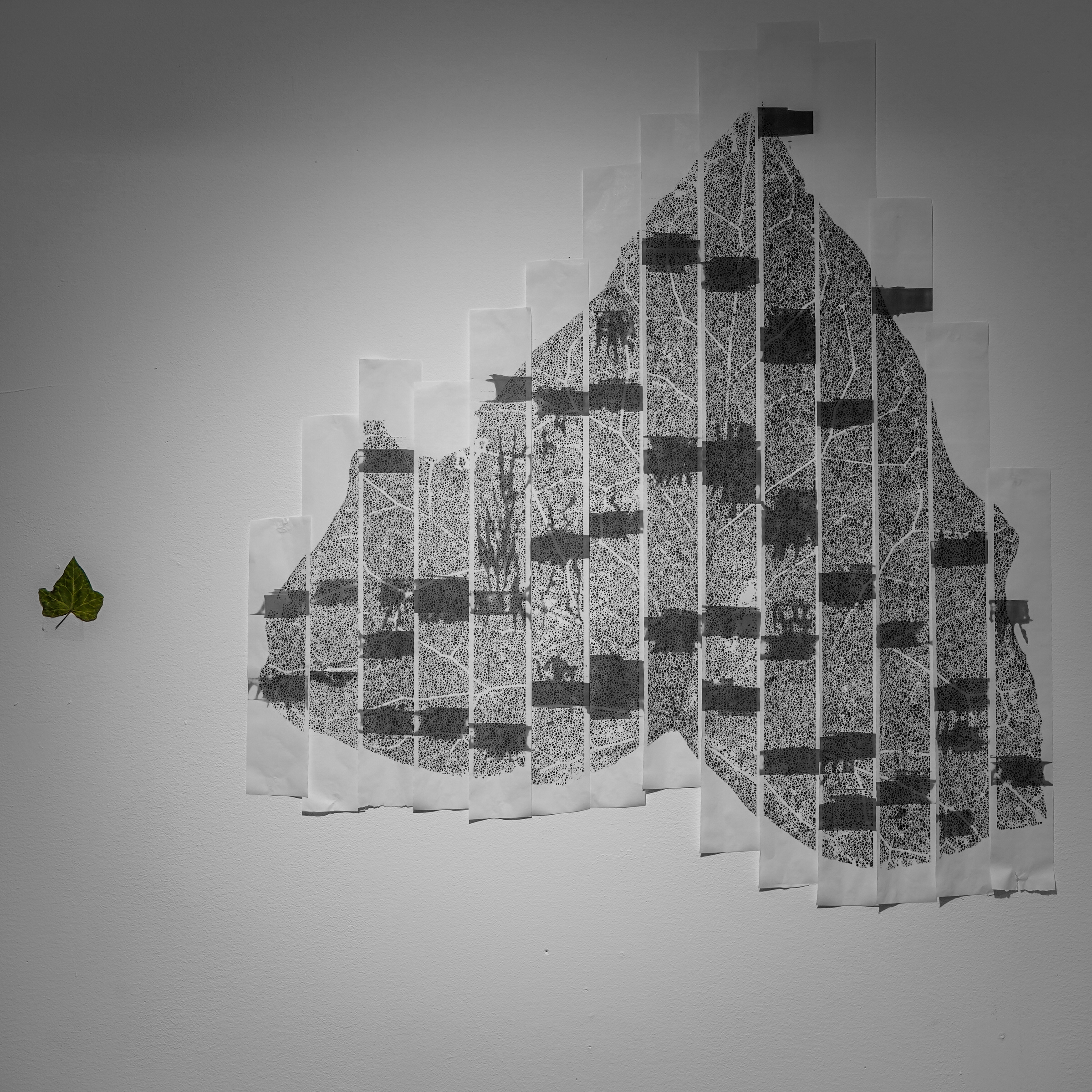

Prints on thermal paper burned by a custom microscope;

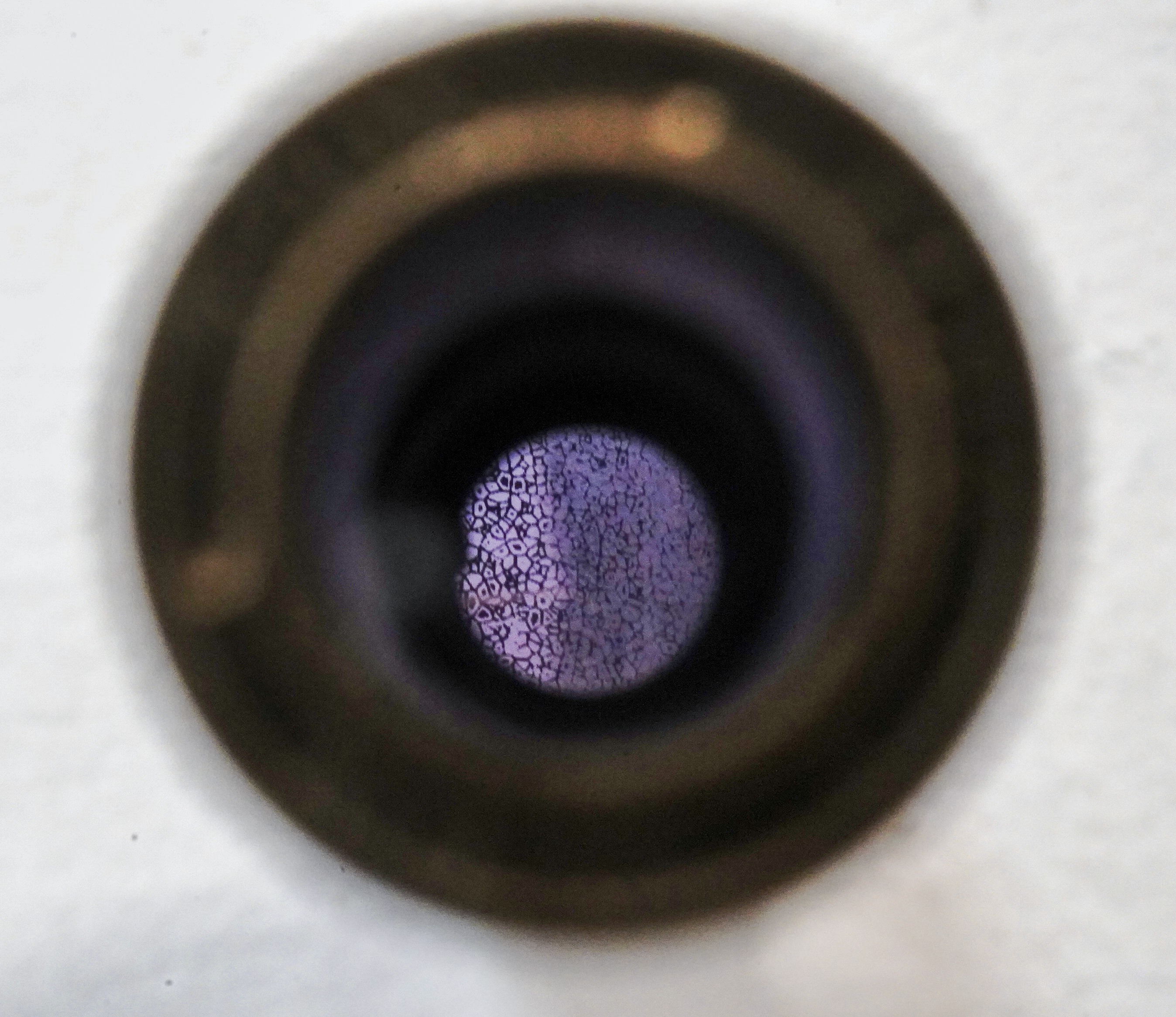

Microscope eyepiece;

Microcontroller and electronics;

Various leaves in sealed containers.

-> sculpture: 15’’ x 15’’ x 45’’

-> prints: 18’’ x 30’’ each

-> Dec. 2022

MicroVision is a multimedia installation consisting of detailed and delicate prints on thermal paper of plant’s cellular structures, and a custom-made microscope that concretizes gazes into burn marks. This work explores the possibilities of recreating plants’ cellular structure with generative algorithms based on the Voronoi diagram, while discussing the specific relationship between the viewer and the object being viewed under a microscope. MicroVision attempts to examine the act of ‘gazing’ in scientific studies, with a particular focus on how the power relationship between humans and plants is exercised with the assistance of scientific instruments.

Several mundane types of leaves’ microscopic photos were taken and stitched together, the result being some ultra-high resolution images. The images were then fed into an evolutionary algorithm designed based on the Voronoi diagram, which adjusts its seeds’ positions and cell regions given the pixel values of the input image. The aim is both to explore the algorithmic potential of reproducing plants’ cell structures, and to recreate the microscopic vision of a leaf without damaging the leaf itself.

The imagery was printed on thermal paper, passed through a mechanism that contains an eyepiece from a microscope, a microcontroller, a light sensor and heating boards. The heating system will be activated when a visitor looks through the eyepiece. The part of thermal paper that is being looked at will gradually be burned and turn black.

-> Video

-> Writing

The Gaze

Gazing – the word connotes a tensionexisting in the mutuality between the subject and object. In consideration of the gaze, we care not only about the act of "looking", but also the mechanisms of looking and the power relationships implied in it.

Gazing is only made possible by light, yet the experience of gazing transcends light itself. “By acquiring the status of object, its particular quality, its impalpable color, its unique, transitory form took on weight and solidity. No light could now dissolve them in ideal truths; but the gaze directed upon them would, in turn, awaken them and make them stand out against a background of objectivity.

Those who grow plants develop a new relationship with light, just as photographers learn to observe light-–a necessity, but also something to be wary of. In photography, too much light--overexposure--will damage the pictures and details will be lost. For plants, too much light will also burn the leaves. The nuances possessed by the object being gazed on affect our understanding of light and the gaze itself.

The distorted microscopic vision emerges from a mechanism of gazing different from that of everyday life. An eyepiece creates an isolated environment, placing the gazing subject and object at isolated positions at both ends of the scope, while the distance between the two is extended to infinity. The microscopic imagery of you only exists for me. You are the only object in my eyes. You and I -- together we enjoy this unique mutual privacy.

Scientists have learned to see less, thus the field of visibility has been narrowed down by a system of strict rules. Observation has to be constructed or at least constrained by a system of rules that determine what counts as an ‘appropriate’ observation. We must learn how to look. In botany, the systematic observation method established by Carl Linnaeus only focuses on the shape, quantity, spatial arrangement and relative magnitude of plant organs, ignoring properties like color or smell for their subjectivity and reliability. “The concept of the gaze highlights that looking is a learned ability and that the pure and innocent eye is a myth.”

A Trap for Gazes

An image detailing the microstructure of a leaf has, in a sense, the same essence as every painting: a trap for gazes. This work attempts to create a dilemma for the viewer: a leaf and its fine microscopic image are laid out at a distance in front of the viewer. Only when one lower their head, looking through the eyepiece, can a clear microscopic image of the leaf’s cell structure be seen. The image under the microscope will react to one’s gaze, gradually turning black and disappearing while being looked at, which in turn documents one’s – a scientist’s or a tourist’s – observation with burn marks. Once the gaze is captured, it will be irretrievably lost to the viewer's eyes at that point (which sometimes reminds us of the relationships between artists and their artworks…). It merges with the subject being gazed on and becomes part of the tangible painting hung on the wall. For Jacques Lacan, this gaze, which constantly reveals itself and then disappears, is essentially our unattainable object of desire.

-> Process & Techniques

-> Image Making

Some leaves’ microscopic photos were taken and then stitched together, the results being several ultra-high resolution synthetic images. The images were later fed as the input of an evolutionary algorithm designed based on the Voronoi diagram, which adjusts its seeds’ positions and cell regions given the pixel values of the input image. The aim is both to explore the algorithmic potential of reproducing plants’ cell structures, and to recreate the microscopic vision of a leaf without damaging the leaf itself.

-> Interactivity

The imagery was printed on a roll of thermal paper, passed through a mechanism that contains an eyepiece from a microscope, a microcontroller, a light sensor (photoresistor) and heating boards. When a visitor is looking through the eyepiece, the photoresistor senses the change of light and activates the heating system. The part of thermal paper that is being looked at, with specific parts of image printed on top, will gradually be burned and turn black. While multiple parts are burned over time, a thermal paper roll documenting the viewers’ gazes is produced by such a process.